The Platinum Group Metals

Here we’re continuing on from our earlier article about recycled and fair trade gold. This time we take a look at the other important group of metals used in making fine jewellery – the Platinum Group Metals.

First, what are Platinum Group Metals (PGMs)?

The platinum bit is obvious, but this group of metals also includes palladium, rhodium, ruthenium, iridium and osmium.

Of these, platinum and palladium are routinely used to make jewellery. (Usually alloyed with ruthenium (5%) and iridium at up to 10%.) Rhodium is often used to plate white gold to keep it bright and shiny. Osmium however, is rarely used in jewellery because it’s very difficult to work with.

PGMs are favoured in fine jewellery because of their high value (due to their rarity), and because of their hypoallergenic properties. (They don’t cause irritation or otherwise react when in contact with the skin.)

The major use for PGMS however is in the automotive industry. Mostly in catalytic converters that remove harmful contaminants from automotive exhaust fumes.

Where do PGMs come from?

In a jewellery making context, PGMs come from one of two sources – mining (or primary production) and recycling.

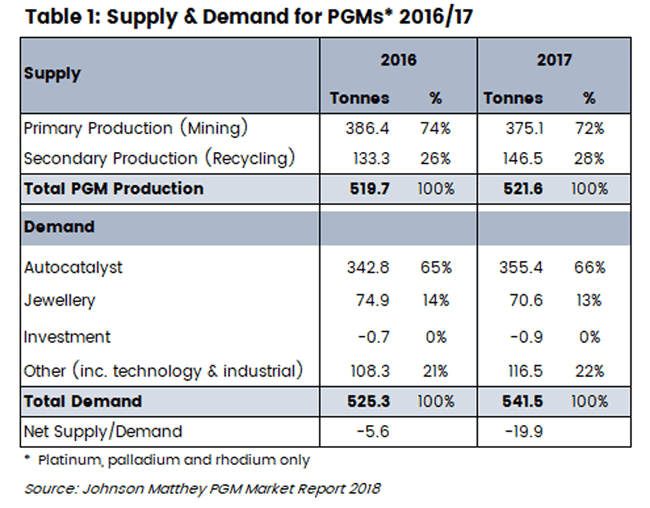

When it comes to mining, South Africa is the major primary producer of PGMs (73% of supply in 2017). Russia is the next largest at 11%. And recycling contributes around about 27% of global PGM supplies (1).

Our choice for jewellery making is always to use recycled PGMs. As you read on it’ll become obvious why that is.

Fair-mined PGMs aren’t really a thing

Unlike in the gold supply chain, fair-mined PGMs aren’t really a thing.

Fair-mined platinum made a brief appearance around 2012/13 when it was marketed by the Fairtrade Foundation in the UK. The metal being sourced from Oro Verde Corporation (Columbia) where it was produced as a by-product of their gold mining operations.

Since then it has essentially disappeared from the market.

Why no fair-mined PGMs?

Fair-mined in the mining sector, be that for diamonds, gemstones or precious metals, almost always relates to Artisanal Small-scale Mining operations (ASMs) in developing nations. Exploitation of miners, criminal activity, adverse health outcomes, child labour and unsafe working conditions are major problems.

For sure gold, diamonds and gemstones are hard work to recover. But PGMs are considerably more difficult to extract from ore-bearing deposits because of their chemical properties.

Mineral concentrations in the ground are typically similar to gold (2). However the technologies required to concentrate the minerals to the point where they can be refined are considerably more capital and energy intensive. And the process itself is much slower, taking up to 6 months end-to-end.

Concentrating gold is often (literally) a home-based activity in ASM communities. This is just not possible with PGMs.

For this reason, there is essentially no artisanal mining of PGMs. Hence the conditions that give cause to the need for ‘fair-mined’ don’t exist.

Recycled PGMs

Recycling of PGMs is commonplace, with automotive parts (catalytic converters) being a major source.

And because of the relatively high concentrations of these minerals in easily identifiable scrap, the recycling processes are considerably more efficient than primary production.

Let’s talk about Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGs)

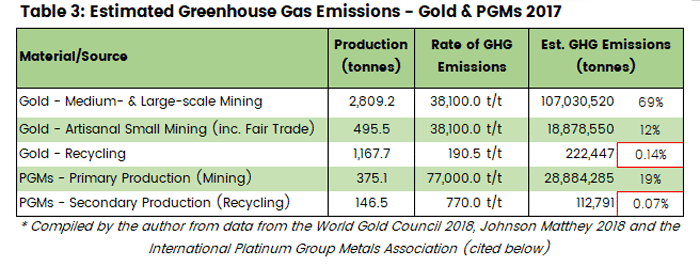

As you’ll recall in our discussion about gold production, our key reason for preferring recycled gold over mined gold (even fair trade gold) was the enormous difference in greenhouse gas (CO2 equivalent) emissions between the two.

Based on figures from the World Gold Council (3), mining as a source emits approximately 38,100 tonnes of CO2e for every one tonne of gold produced. Whereas recycling emits approximately 190 tonnes of CO2e for every tonne of recycled gold.

That’s a whopping 200 times fewer emissions per tonne produced!

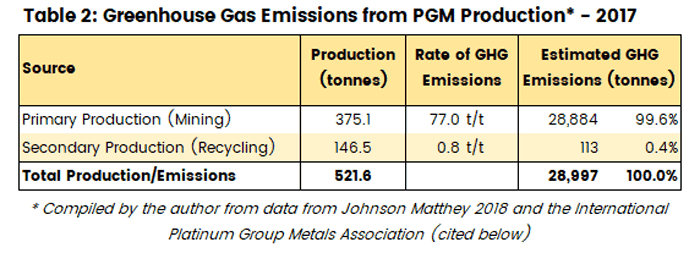

When it comes to PGMs, according to a paper submitted to the World Congress on Engineering in 2015 (4), in South Africa at least, primary production of PGMs emits CO2e at the rate of approximately 77,000 tonnes for every one tonne of PGMs.

That’s almost double the rate at which primary gold production emits CO2e.

A big part of the reason for this is that South Africa generates 95% of its electricity from coal-fired power stations and electricity consumption represents approximately 72% of the overall GHG emissions from mining and processing (4).

And given that South Africa produces 73% of the world’s supply of PGMs, you can see where the problem lies.

(Russia – the world’s second largest PGM supplier – generates approximately 63% of its electricity from gas and coal-powered thermal generators, 21% from hydro and 16% from nuclear power plants (5)).

How does recycling stack up?

According to a study by the International Platinum Group Metals Association (IPA) using data from the early 2010s, recycling PGMs contributes to the generation of GHGs at about 1% of the rate primary production does (6).

What that means is if primary production of PGMs yields 77,000 tonnes of CO2e per tonne produced, recycling yields approximately (only) 770 tonnes of CO2e per tonne recovered.

A big contributor to this vastly better emissions performance is the concentration of PGMs in scrap vs the concentrations found in mineral bearing ores.

Mineral-bearing ores typically yield between 2 and 6 grams of PGMs per tonne. Recycled catalytic converters (in North America) yield in the order of 2,000 grams per tonne. That’s between 330 and 1,000 times more per tonne (7).

Plus, you have the added benefit of greener energy sources in developed countries where a lot of recycling takes place.

When you look at the ratios for GHG emissions tonne for tonne for recycled vs primary production, it’s obvious which is the better way to go.

Recycling accounts for around 27% of PGM production, yet yields less than 0.5% of GHG emissions (estimated). And given Fair Trade is a non-issue, preferring recycled platinum and palladium over mined PGMs is a no-brainer.

What about green-washing?

Green-washing is often mentioned as a reason for being suspicious of recycled precious metals, or even to avoid them.

It’s the process by which illegally sourced material (from illegal mining, theft, fraud, money laundering etc.) enters the supply chain at the point of recycling. It’s then on-sold as ‘legal’ recycled metal.

Placer deposits of PGMs – usually alluvial – are extremely rare and, as a result, ASM (especially illegal ASM) is almost unheard of. In turn, criminal activity at the mine site (so to speak) is virtually non-existent.

Bigger problems arise downstream, particularly at the smelter and concentrator stages where theft becomes an issue (8).

Lower grade material stolen in South Africa typically re-enters the supply chain via refineries in Europe.

It’s estimated that green-washing might affect up to 1% of global PGM production which, in turn suggests that 3-4 tonnes of PGMs might be green-washed each year. (Around 3% of global recycling output.)

As it is with gold, avoiding green-washed PGMs means being careful when choosing your supplier.

For recycled platinum, we use a local, Gold Coast-based refiner (Precious Metal Technologies), and for recycled palladium (and platinum pressed metal rings and jewellery findings) we use Hoover & Strong, a US-based refiner. Both have verifiable, legal sources of scrap. We also reuse our own (and customer supplied old jewellery if suitable) scrap and refine in house.

Primary production vs fair-mined vs recycled – which to choose?

In this and our earlier article, we’ve explored the pros and cons of various sources of gold and platinum group metals for use in jewellery.

When it comes to PGMs, for us it’s pretty cut and dried. In the gold supply chain, it’s a little more complicated. (Though it depends on which hat you wear.)

If you put on your environmentalist hat and consider relative greenhouse gas emissions (never mind pollution and habitat destruction), then it’s an objectively easy decision:

Based on the rate of GHG emissions, the recycled options are the stand-outs.

Now, if you put on your social-responsibility hat however, it’s not such an easy choice to make. At least when it comes to gold.

When you consider the well-being of small mining communities and the need for development in emerging economies, it’s not quite so easy to write off fair trade gold as an option.

Per tonne produced, gold is a heavy polluter when it comes to GHGs. But in terms of total tonnage per annum of CO2e, it’s a relatively small player (at 126 million tonnes)*. Likewise, PGMs are (at 30 million tonnes) not a big contributor on a global scale*.

*By comparison, steel production generates around 3,750,000,000 tonnes of CO2e per year (3). That’s 24x the output of gold and PGMs combined.

Give me some numbers I can relate to!

All this talk of millions of tonnes of CO2e and hundreds of tonnes of precious metals is probably hard for the average person to wrap their head around.

Very few of us are likely to bump into one kilogram of gold, much less one tonne! So let’s use some measures that are a bit more familiar.

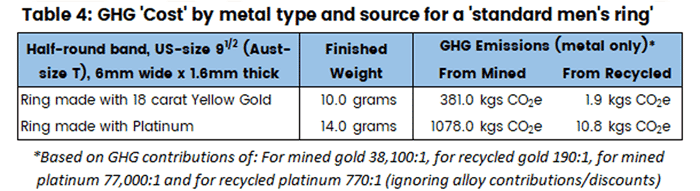

Take an average (men’s) plain wedding ring for example – say, half round, size US 9½ (Aust-size T), 6mm wide x 1.6mm thick.

This ring would weigh around 10 grams if made with gold and around 14 grams if made with platinum.

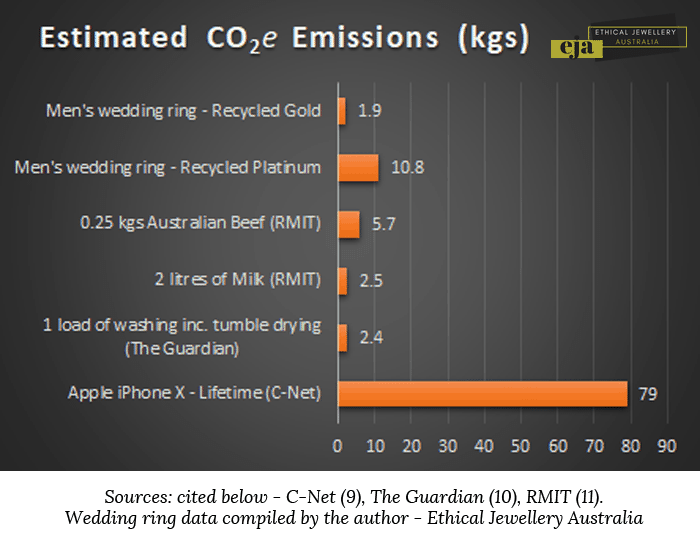

If we look just at the GHG emissions relating to that amount of metal (ignoring manufacturing, alloys, packaging and transport), Table 4 below shows how much CO2e would be produced based on the source of the metal.

From this, a ring made with recycled gold is clearly the most environmentally friendly option. (From the point of view of where the metal comes from.)

At the other end of the scale, a ring made with primary mined platinum is hideously expensive GHG-wise. You’re looking at more than a tonne of CO2e for just one ring!

But how does this stack up against other day-to-day things?

The following chart gives you an idea of how some everyday items compare with our men’s ring example above:

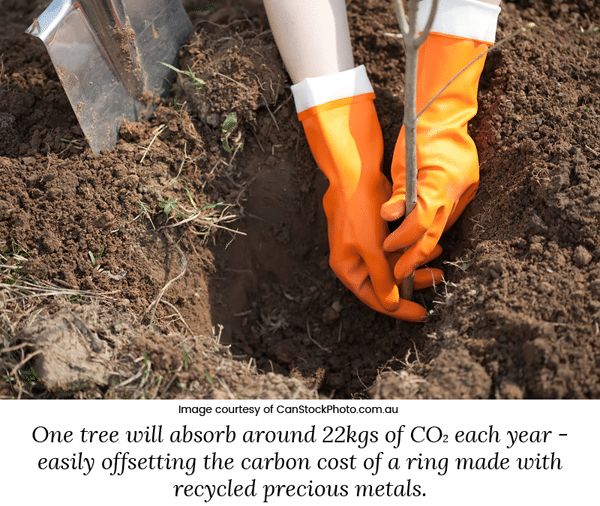

The reality is you don’t need to do a whole lot to off-set the carbon cost of a piece of quality jewellery, provided it’s made with recycled precious metals.

In fact, if you want to easily offset the carbon cost of your jewellery made with recycled metal, go plant a tree. According to NC University’s Department of Horticulture (12) the average tree will absorb around 22kgs of CO2 per year.

It requires quite a lot more effort (and a lot more trees) if you settle for mined metals however.

Where does EJA sit?

As we’re sure you’ve figured out by now, our feet are firmly planted in the recycling camp. When it comes to PGMs and jewellery it’s very hard to justify mined platinum and palladium over recycled. Especially when the recycled product is identical in all aspects!

As for gold, our first preference is again recycled simply because of the carbon cost weight-for-weight. But if you want fair trade gold, we’re happy to oblige because the social benefits give some balance to the carbon cost.

References & More Reading:

- Johnson Matthey PGM Market Report May 2018: http://www.platinum.matthey.com/documents/new-item/pgm%20market%20reports/pgm_market_report_may_2018.pdf

- The Environmental Costs of Platinum-PGM Mining: An Excellent Case Study In Sustainable Mining, 2009: http://users.monash.edu.au/~gmudd/files/2009-CMS-02-Platinum-PGMs-v-Sust.pdf

- Gold and Climate Change: An Introduction (World Gold Council, 2018): gold.org/download/file/6812/gold-and-climate-change-report.pdf

- Quantifying CO2-equivalent emissions of ore-based PGM Concentration Process in South Africa and identification of Immediate Environmental Impacts – Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering 2015 http://www.iaeng.org/publication/WCE2015/WCE2015_pp863-865.pdf

- Energy in Russia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_in_Russia

- The Environmental Profile of Platinum Group Metals, IPA: https://ipa-news.com/assets/sustainability/Environmental%20Profile_LR.pdf?PHPSESSID=86216a7ceff02ff3201d4a79532a300c

- Recycling Today Magazine: http://magazine.recyclingtoday.com/article/january-2018/pgms-scrap-demand.aspx

- Strengthening the Security and Integrity of the Precious Metals Supply Chain – United Nations Inter-regional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), 2016: issuu.com/unicri/docs/precious_metals_report

- C-net, 2017: https://www.cnet.com/news/apple-iphone-x-environmental-report/

- The Guardian Newspaper, 2010: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/green-living-blog/2010/nov/25/carbon-footprint-load-laundry

- RMIT University, 2016: https://www.rmit.edu.au/news/all-news/2016/november/new-study-provides-carbon-footprint-league-table-for-food

- NC University – Dept. of Horticulture: Tree Facts

You might also want to read our article about choosing the right precious metal for your rings.

About EJA

Ethical Jewellery Australia is an online engagement and wedding ring specialist. Every ring is custom designed and made to order.

We take our customers through the whole process from design to sourcing and finally to manufacturing.

All rings are handmade in Australia with recycled metals. (We can also supply fair trade gold if requested.)

Likewise, we only every use ethically sourced diamonds and gemstones. You can choose from Argyle, recycled, vintage and lab-grown diamonds, Australian, US, Fair Trade, recycled and lab-grown coloured gemstones.

By the way, we offer an Australia-wide service.

If you would like to learn how to start your engagement ring design adventure, get in touch today.

If you would like to learn more about designing an engagement ring, download a copy of our free 70+ page design guide.

If you would like to learn more about designing an engagement ring, download a copy of our free 70+ page design guide.

About the Author: Benn Harvey-Walker

Benn is a Co-founder of Ethical Jewellery Australia and a keen student of ethical and sustainability issues in the jewellery world. He has a long history in sales and marketing and began working with EJA full time in early 2018.

Benn is a Co-founder of Ethical Jewellery Australia and a keen student of ethical and sustainability issues in the jewellery world. He has a long history in sales and marketing and began working with EJA full time in early 2018.

Benn co-authored the original Engagement Ring Design Guide in 2014 and edited the 2nd Edition in 2018. He is also the principal author of the wedding and commitment ring design guide.

His main responsibilities at EJA are business development and sales process management. Benn also creates technical drawings for our ring designs.

Recent Comments