Twenty-something years ago, if I’d posed the question: “Can one diamond be more ethical than another?”, I’m confident I would’ve received a lot of blank stares as my answer.

Back then few consumers would have put the words ‘ethics’ and ‘diamonds’ in the same sentence. Not because diamonds were necessarily unethical, it’s just that no one gave it a second thought.

Gladly, we’ve come a long way since then.

Awareness that ethical choices can (and should) be made when it comes to diamonds and diamond jewellery has skyrocketed in recent years.

This is a good thing.

Awareness of an issue is the first step towards positive change.

But with awareness comes the potential for confusion and being misinformed. Information consumers are exposed to can be biased, incomplete or, sometimes, just plain wrong.

You, as a potential buyer of diamonds, have more information available to you than ever before. And as it is with most things, the more choices you have, the harder it is to decide.

What’s the right choice for you?

Assuming you want a diamond (and not a diamond alternative like moissanite), these days you have three options:

- Diamonds that come out of the ground;

- Laboratory-grown diamonds; or

- Recycled or ‘vintage’ diamonds.

Traditionalists will tell you mined diamonds are the way to go.

Why? Because, well, they’re traditional and mined diamonds are ‘real’, and we’re told they’re ‘rare’. We’re also told they’re romantic, that diamonds are a girl’s best friend and some of them fetch record prices at exclusive auctions.

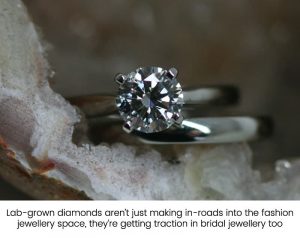

However, despite the power of tradition and romance, indications are younger buyers are increasingly favouring option number 2: laboratory-grown. (Principally because they are believed to be a sustainable product and they do represent good value for money.)

Meanwhile, those committed to reducing the impact of unnecessary consumption will advocate for recycled and vintage diamonds. (Which also tend to offer great value for money.)

Ultimately, which of those makes for the ‘best choice’ really comes down to your own personal ethics. And, unless money is of no concern to you, your decision will probably also include some financial considerations.

The right choice as a function of your personal ethics

The subject of ‘ethics’ in the context of the diamond industry is complex – to say the least.

As is the case for a lot of ethical discussions, ethics is personal. What you object to, I might be perfectly fine with. On the other hand, a third person might think the subject we disagree on is not even an issue.

It’s complicated, so let me see if I can help you through the fog.

What are the big issues?

The two big, broad categories that most ethical issues in relation to diamonds and diamond jewellery fall into are:

- Human rights; and

- Environmental concerns.

Once you delve into these in any real depth, you’ll soon discover they overlap quite a lot.

The Mined-diamond Industry

It would be very easy to spend the next ten minutes detailing the historical transgressions of the mined diamond industry and highlighting the many issues that still exist.

Likewise, it would be just as possible to cherry pick a bunch of good news stories and paint the industry in a glowing light.

But the purpose of this article isn’t to make you love or hate the diamond mining industry.

The purpose of this article is to make sure you’re aware of the positives and negatives so you can do further research if you want, develop your own views and make decisions that feel right for you.

A quick internet search will turn up plenty of examples of habitat destruction, human rights abuses and criminal enterprise in the diamond industry. But on the other side of the same coin you can find significant social benefits attached to economic development and employment.

On the face of it, it would be very easy to dismiss diamond mining as a bad idea for environmental reasons alone. But the humanists among us find it’s not easy to just write off millions of people throughout the supply chain who, in many circumstances, have no other choice when it comes to earning a living.

Is ‘traceability’ the solution?

There’s no getting past the fact that much of the unpleasantness attached to mined diamonds is linked to their point of origin and the route they take to market.

Being able to trace diamonds back to where they came from (through technologies like Blockchain) is being lauded as the best way to assure consumers the diamonds they purchase aren’t tainted by things like conflict funding, slavery, child labour, smuggling and money laundering.

To my mind, ‘traceability’ – whilst a step in the right direction – has the potential to become the new “Low Fat” in food marketing. Put that sticker on your product and all the other sins are washed away.

But is that enough?

Suppose the diamond you want to buy is traceable back to its point of origin in, say, Canada.

Sounds good. There’s no civil war in Canada. Citizens are protected by the rule of law. Workplace safety is enforced and there’s no child labour. Tick, tick, tick and tick.

But with just a little inside knowledge, some nagging questions pop up.

But with just a little inside knowledge, some nagging questions pop up.

How is the mine in Canada affecting the local area? Is it damaging vulnerable local ecosystems? Is it disrupting migration patterns of wildlife in the region? Does it produce a disproportionate amount of carbon emissions because of where it’s located? Are the local indigenous peoples receiving their fair share of the wealth being created?

And what about the cutting and polishing process? Where was it done? Were those artisans well treated and paid appropriately? Are the cutting factory owners able to earn enough to do the right thing by their employees and their community?

Just knowing the point of origin is not enough.

And even knowing the route the diamond took to market isn’t enough on its own either. The devil is in the detail.

Like I said. It’s complicated.

Most diamonds on the market today aren’t traceable anyway

By the way, it’s important you know that most mined diamonds on the market today are not traceable to their point of origin.

Traceability is a relatively new thing, still in its infancy.

And just because some diamonds can now be traced back to where they were dug up, that does not mean they all can be. Far from it.

It will be a long time before the untraceable diamond ‘lump’ has passed through the snake.

Choosing mine-origin diamonds doesn’t guarantee benefits to those who need them most

Artisanal small-scale miners (ASMs) contribute around 20% of the global diamond supply. But once the diamonds they produce enter the supply chain, they get added to millions of other diamonds produced around the world by large scale mining enterprises and thereafter become untraceable.

Artisanal small-scale miners (ASMs) contribute around 20% of the global diamond supply. But once the diamonds they produce enter the supply chain, they get added to millions of other diamonds produced around the world by large scale mining enterprises and thereafter become untraceable.

At this point in time there is no Fair Trade certification scheme for diamonds. This means (unlike Fair Trade gold and many Fair Trade coloured gemstone varieties) you cannot purchase a mined diamond and know a portion of the money you spent will go back to a mining community somewhere in a developing nation.

That’s not to say it doesn’t. It’s just that you cannot yet actively make that choice.

What’s the answer?

It doesn’t really matter which way you turn, any choice you make when it comes to buying mined diamonds will be a compromise. But at least you’re making an informed choice.

Where does Ethical Jewellery Australia stand?

Our own choice, when it comes to mined diamonds, is only to offer West Australian origin diamonds from the Argyle and Ellendale mines.

The mine operators adhere to strict environmental and employee safety standards, work closely with the local indigenous communities and take great care to ensure their diamonds are cut in factories that treat their employees well.

They also go to great pains to ensure their diamonds are quarantined in the supply chain, so they are traceable.

How does this help struggling communities in Africa, Asia and South America?

It doesn’t, directly. But we’re choosing to support those people indirectly by working with charitable organisations (like Pactworld.org) dedicated to education, infrastructure and economic development in places where diamonds, gemstones and precious metals are sourced.

We also choose to fund the planting of trees and shrubs in several habitat regeneration projects in Western Australia to help off-set our carbon emissions. (Through an organisation called Carbon Neutral Charitable Fund.)

Perhaps that’s an option for you too? To consider what a supplier does to give back as well as evaluating what they sell?

The Laboratory-grown diamond Industry

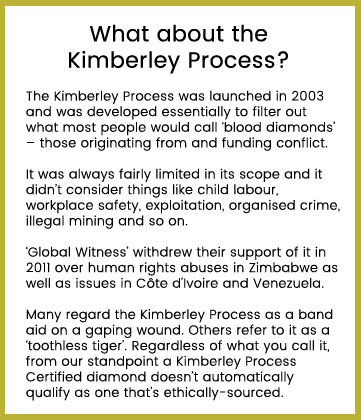

Lab-grown diamond (LGD) producers are currently riding a wave of environmental awareness – one that’s driven by market concerns about climate change.

Lab-grown diamond (LGD) producers are currently riding a wave of environmental awareness – one that’s driven by market concerns about climate change.

Through some innovative (for the diamond industry) marketing, they’ve managed to grab the attention of consumers concerned about their carbon footprint.

To the mined diamond industry, they represent a ‘triple threat’. Not only do LGDs appear to have much better environmental credentials, but they’re also cheaper and don’t carry the same human rights abuse baggage that burdens the mined-origin sector.

From a consumer’s perspective, lab-grown looks like a great option from both social and environmental viewpoints, but it’s important you appreciate that not all lab-grown diamonds are created equal.

Some lab-grown diamond producers have great environmental credentials. For the majority however, who knows?

Just because it’s laboratory-grown, that does not automatically mean it’s all clean and green.

Where the electricity comes from matters

Recently I read about a laboratory-diamond manufacturer that proudly mentioned how they source their electricity from wind turbines.

On the face of it that sounds good, however wind turbines are notoriously unreliable generators of power. They’re much too unpredictable for the process of diamond manufacturing which demands a constant supply. Yet there was no mention of where else the electricity comes from.

Perhaps those turbines feed batteries, or maybe they just feed into the grid? We don’t know.

The factory is based in India which (according to Wikipedia) gets 80% of its electricity from burning coal. In other words, there’s a fair chance the carbon footprint of those particular LGDs is higher than we’re led to believe.

On the human rights side of things though, the lab-grown diamond sector isn’t under the same cloud as the mining industry – at least on the manufacturing side (as far as we know).

That said, it’s worth noting that very many LGD factories are sited in China and India where labour is abundant and cheap.

Few LGD producers talk about how they treat their workforce.

That might be because everything is hunky-dory and it’s a non-issue. Or it could be that no one has asked the question? Again, we don’t really know for sure.

The problem is, no one is demanding answers. Instead they’re applying the same kind of “Low Fat” sticker that traceability pundits in the mining industry are set to benefit from.

And then there’s cutting and polishing

LGD factories produce large diamond crystals that need to be cut and polished.

Some do that in-house, but many lab-grown diamonds are processed in the same cutting factories as are mined diamonds.

So that begs the question; What are the conditions like for the cutters and polishers?

Maybe they’re relatively good? Maybe they’re not?

You can’t just assume that because a diamond is laboratory-grown, it’s all good.

It might not be.

Let’s talk ‘carbon footprint’ for a moment

If your only measure of ethical performance is carbon footprint when judging mined- against lab-grown, then there’s still no clear winner.

In 2018 the International Grown Diamonds Association (IGDA) promoted the claim that growing diamonds in a laboratory produces far fewer greenhouse gas emissions than does mining. As time goes by it’s becoming evident that this might only be true for some producers.

There are three significant variables when it comes to energy usage in lab-grown diamond production: the method, the age of the technology and the source of the electricity used.

Two methods are used to create diamonds in commercial quantities: High Pressure, High Temperature (HPHT) and Carbon Vapour Deposition (CVD).

CVD is more efficient than HPHT and generally, the younger the technology, the more energy efficient it is.

The source of the electricity is the kicker

Though there is a big variation in efficiency between the ages and types of production technologies, where the electricity comes from is far more important.

If the electricity comes from coal-fired power stations, it’s not good news.

In the US, coal-fired power stations emit greenhouse gases (GHGs) at the rate of around 1kg per Kilowatt Hour (KwH).

At the other end of the scale, hydro-electricity yields only around 0.004kgs of GHGs per KwH. (Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – IPCC, 2011.)

Energy usage by LGD producers varies wildly

In an article titled “Just how eco-friendly are Lab-created diamonds?” published in JCK News Daily this month, the author Rob Bates reported that energy usage to produce a one carat of rough lab-grown diamond could be anywhere between 60 and 225KwH.

If all that electricity came from coal, then you’re looking at a minimum 60-225Kgs of GHGs per carat of rough diamond produced. However, if hydro was exclusively the source, GHG emissions could be as low as 0.24kgs to 0.9kgs per carat.

How do mined diamonds compare?

Mined diamond rough carries a carbon cost of around 57kgs per carat on average (Frost & Sullivan, 2018).

The extremes in this measure can vary widely too, ranging from 7kgs per carat to the low end to around 80kgs per carat at the high end. But overall you’d have to say mined diamonds appear to compare favourably with lab-grown in terms of carbon cost – all things considered.

It’s true that some lab-grown diamonds could have a very small carbon footprint. But that’s also true for some mined diamonds.

Is Carbon Footprint a meaningful measure?

Short answer; yes – but only if you have access to the relevant information.

Transparency is the key for both lab-grown and mine-origin producers.

Ultimately, it’s all about where the electricity comes from. (By the way, it’s important to acknowledge the diamond mining industry is taking big steps towards improving its efficiencies.)

Does the LGD sector occupy the ethical high ground relative to mined diamonds?

If you’d asked me this question 12 months ago, my answer would’ve been a qualified ‘yes’ – based on the available information at the time.

Now that more information is coming to light, in the context of the two big issues mentioned at the outset (human rights and environmental concerns), I’d have to say the following:

- When it comes to the environment, you must choose your supplier carefully. LGDs could be much better, but they could also be much worse than an equivalent mined diamond; and

- When it comes to human rights, given the disproportionately large of number of people who are mistreated or do not benefit equitably from the diamond mining industry, I’d say LGDs are more ethically sound – socially anyway.

But that’s just my opinion.

What’s right for you depends entirely on your personal ethics.

The thing is, by many standards, both laboratory-grown and mined-diamonds can be relatively ethical or relatively unethical.

It’s a question of what’s important to you.

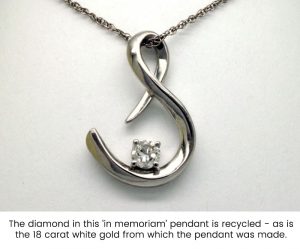

And then there’s Recycled and Vintage Diamonds

Recycled and vintage diamonds almost certainly offer the ‘greenest’ option of the three available to you.

Recycled and vintage diamonds almost certainly offer the ‘greenest’ option of the three available to you.

That said, once again you need to check your supplier carefully.

Not only do you need to be sure the diamonds come from verifiable, legal sources, but you also need to check that the stones you’re buying aren’t from remaindered stock.

Remaindered stock typically features ‘new’ diamonds that couldn’t be sold in whatever piece of jewellery they were originally set into. It’s common to “recycle” remaindered stock into new product. In this instance however, recycled does not necessarily mean ‘post-consumer’ (or pre-owned).

“Show me the money!”

No balanced discussion about buying diamonds can take place without giving at least some consideration to the role money plays when making a purchasing decision.

It’s easy to get a soap box and say you should buy one thing over another for these various ethical reasons. But that assumes money isn’t an issue.

For most people however, cost is an unavoidable consideration.

When it comes to price competitiveness, lab-grown has a significant price advantage, selling at around two-thirds the price of mined stones.

Once you get into larger stones that can translate into hundreds, if not thousands of dollars saved. It’s certainly enough to sway a lot of buyers.

Recycled (modern cut) diamonds tend to sit somewhere between lab-grown and mine-origin diamonds, so there’s money to be saved there too if lab-grown isn’t your thing.

When it comes to vintage diamonds however, it’s very difficult to compare apples with apples.

Vintage diamonds (usually from the early 1900s) are cut differently and are typically higher coloured. In many respects they’re not really the same product we get these days.

On balance though, vintage diamonds tend to sit below the cost of a “similar” lab-grown diamond.

What about resale value?

Unless you really know what you’re doing and have the financial wherewithal to purchase truly extraordinary diamonds, the advice is simple: Do not buy a diamond because you think you might be able to get your money back sometime in the future.

(And frankly, if one of your big decision criteria when buying an engagement ring is whether you’ll get your money back if you must sell it, maybe you should rethink the idea of getting married!)

Buying diamond jewellery is a lot like buying a new car. Once you take it out of the showroom, its value drops dramatically.

There are exceptions of course, just as there is in the automotive market, but generally you cannot bank on getting back anything like what you paid. (Presently in the US, second-hand diamonds trade at about 35% of their original retail value.)

Because there’s no large-scale formalised second-hand diamond market, when you try to resell a diamond it’s a matter of taking what you can get.

Of the available options your best bet when it comes to preserving value is to go with a ‘branded’ rare colour or a very high quality or otherwise remarkable mined diamond. For example, pinks produced by Argyle in Western Australia or a ‘D flawless’ diamond over several carats.

Jewellery-quality Argyle diamonds have robust environmental and social credentials, are priced as a premium product and are in reducing supply. The mine will probably cease production in 2020, so Argyle diamonds will no longer be available as new once any stockpiles have been exhausted.

This may help to maintain their long-term value, but there are no guarantees.

Of course, if you’re buying off-the-shelf diamond jewellery, go with a well-regarded, up-market brand as the value is tied up in more than just the diamonds.

Recycled and Vintage Diamonds

Recycled/vintage diamonds are probably a reasonably good option too in terms of preserved value.

The problem is though, as mentioned above, there’s no formal, transparent second-hand market for diamonds.

With cars at least you can go on-line and see what the going price is for what you want to sell. That’s not an option when it comes to diamonds. (Not yet anyway.)

Reselling lab-grown diamonds

As for the resale value of lab-grown diamonds, they haven’t been around long enough in large enough quantities to be able to judge whether they have any significant resale value. For now, it’s probably safest to assume they don’t.

But then again, branding could have a part to play in maintaining value – as is the case with a lot of consumer products. Only time will tell.

So how do you make an ethical choice?

When you look at the available options: mined-origin vs laboratory-grown vs post-consumer, it’s not an easy choice to make.

There are so many grey areas and it seems that no matter which way you lean, someone (or the environment) loses out.

We can’t tell you which is right or wrong. All we can do is give you the information so you can make an informed decision.

Does your supplier share your values?

Because you’ve read this far, I’m going to assume you care one way or another about the ethics of the jewellery you buy, so what advice can I give you?

I think the best suggestion I can make is to look past the first impressions of all the bright and shiny jewellery and ask this about the company or person you’re thinking about buying from:

“Does the person who owns this business care about the same things I care about?”

When it comes to the jewellery industry (in Australia at least), many jewellers and jewellery retailers haven’t moved on from where they were twenty years ago.

As far as they’re concerned, the ethical qualities of the jewellery they make and sell aren’t a thing consumers should worry their heads about – or otherwise it’s something they dismiss as a fad.

Fortunately however, there’s a growing number of jewellery business owners out there who genuinely give a damn. (At Ethical Jewellery Australia, we certainly do.)

So perhaps that’s where your search for the perfect diamond should begin? Find a supplier who aligns with your values and go from there?

They’ll help find the right diamond for you – regardless of whether it’s mine-origin, laboratory-grown or pre-owned.

About EJA

Ethical Jewellery Australia is an online engagement, wedding ring specialist and bespoke jewellery specialist. Every piece we do is custom designed and made to order (with the exception of simple wedding and commitment rings that are offered in a range of simple, popular designs).

We take our customers through the whole process from design to sourcing and finally to manufacturing.

All rings are handmade in Australia with recycled metals. (We can also supply Fair Trade gold if requested.)

Likewise, we only every use ethically sourced diamonds and gemstones. You can choose from Argyle, recycled, vintage and lab-grown diamonds, Australian, US, Fair Trade, recycled and lab-grown coloured gemstones.

By the way, we offer an Australia-wide service.

About the Author: Benn Harvey-Walker

Benn is a Co-founder of Ethical Jewellery Australia and a keen student of ethical and sustainability issues in the jewellery world. He has a long history in sales and marketing and began working with EJA full time in early 2018.

Benn co-authored the original Engagement Ring Design Guide in 2014 and edited the 2nd Edition in 2018. He is also the principal author of our Wedding and Commitment Ring Design Guide.

His main responsibilities at EJA are business development and sales process management. Benn also creates technical drawings for our ring designs.

Recent Comments